When I first heard of Michael Licona’s Why Are There Differences in the Gospels?, I was intrigued. I read some about his literary device view. For instance, the example I remember is spotlighting, essentially focusing the spotlight on one person in the story. That makes sense to me. I figured that if the gospel authors used certain literary devices that were acceptable in their day, then I wanted to understand how they wrote the gospels. While I still have not read Licona’s Why are There Differences in the Gospels?, Lydia McGrew’s The Mirror or the Mask? takes direct aim at his (and others’) claim about the gospel authors’ uses of literary devices.

Setting the Stage

In the preface, McGrew helps orient the reader, “From the outset, I have had several questions in mind: 1) If true, how much would this claim affect our understanding of the reliability of the Gospels? 2) Does independent, non-biblical evidence support the claim that these compositional devices were indeed known and widely accepted in secular literature that is relevant to our understanding of the Gospels? 3) Does the evidence from the Gospels support the claim that the Gospel authors themselves used such compositional devices?” [1]

Part one of the book is focused on setting the stage. McGrew argues that this is an important subject. For one, it affects our understanding of the historicity of the gospel. When I talk about the Great Commission and the importance of spreading the gospel to the nations, can I really say “as Jesus said…”? In chapter one, McGrew gives 20 examples like this. Second, and out of order for the book, she argues in chapter four that this affects one’s view of inerrancy. While McGrew herself does not accept inerrancy, she wonders what the concept could even mean given these literary device views.

Chapter two helps set the stage by making “a handful of crucial distinctions.” One can either write without a state chronology or with a false chronology. What we normally accept as paraphrase is also different than how expansive the meaning is for how “paraphrase” is often used. Another distinction is called transferral. One form of this we accept. If someone said “Brett asked me for money” that is perfectly acceptable even if they mean that I asked them for money through a mutual friend. However, if they said “Brett asked me for money, and his face showed he really needed it”, it’s clear that I better have been there in person asking for money. Finally, there is that tricky word, reliability. Here is McGrew, “Expressed non-technically, this minimal reliability condition is that the testimony is more likely if what it attests is true than if what it attests is false.” [2]

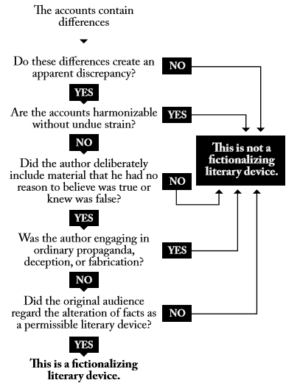

In chapter three, McGrew highlights the importance of the discussion with a bunch of quotations from differing scholars, from Licona to Keener and beyond. The goal is to illustrate that these proponents are proposing what McGrew calls fictionalizing devices. Fictionalizing devices are when an author deliberately changes the facts in a way that the audience would not be able to pick up on simply from reading the text itself. So here is a quote from Licona to illustrate, “John appears deliberate in his attempts to lead his readers to think the Last Supper was not a Passover meal”. [3]

Then comes the meat of the book. Here I will simply set the stage, use a handy chart from McGrew, and then give an overview.

Competing Models

Lydia McGrew is a proponent of Bayesian epistemology. Here is a brief summary of how that works. Consider the proposition “the gospels use fictionalizing literary devices.”

First, you have the prior probability. This is the probability of the proposition in light of our background knowledge. So, for example, if we knew that all (other) extant literary texts from the ancient world use these devices, then our probability would be higher than otherwise.

Second, you also want to take into account new information as it comes to light. So if we found a bunch of manuscripts of Matthew that become the earliest and best and it includes a footnote where Matthew defines the literary device in question and states that he is using it at that place, then that should affect the probability we assign to the proposition.

This is relevant because this is how McGrew assesses the claim that the gospels use these literary devices (note: this is simply her way of thinking through it; it is perfectly readable even if you have never heard of Bayesianism before). For instance, look at this handy chart from McGrew: [4]

Here she parses the different aspects that must be true to make the literary device true. Then she charts it as a decision matrix. Let’s go into more detail on how this works.

Again, first, we want to consider the prior probability that the gospels use these literary devices (part two). If the gospels are ancient biographies and these literary devices are common in ancient biographies, then that raises the prior probability. However, McGrew argues that there is no good reason to believe that the gospels are ancient biographies. Essentially, one would need to establish that the gospel authors were aware of this genre and there is evidence that confirms that the authors wrote within that genre. However, we simply do not have that evidence.

Another factor that could affect our prior probability is if other ancient authors wrote about and used these literary devices. But, McGrew argues, that simply is not the case. For one, the facts that are supposed to support ancient authors writing about these literary devices do no such thing. For instance, writing speeches about what a historical person could have plausibly said at a certain place does not entail that ancient authors encouraged making up speeches. As McGrew points out, you will find similar assignments in English textbooks but we are not teaching our kids to make these things up.

Part of McGrew’s argument, then, is that the prior probability is low for the gospel authors using fictionalizing literary devices. The evidence simply does not bear out what proponents claim. There is, however, another model: the honest reportage model (part 3). Under this view, the gospel authors are trying to write about how things really happened. This makes sense in light of other New Testament evidence (1 John 1:1-5, for instance, claims to be eyewitness testimony about something really true), undesigned coincidences, and more.

However, there is still the gospel evidence that we must assess. The new evidence can make us adjust our probability assessments in big ways. For instance, even if the prior probability is low, this does not entail that the probability is low once we take into account the new evidence. In fact, it could end up being exceptionally high. So, what about the actual gospel evidence?

McGrew’s approach, once again, is to be comprehensive (part 4). She goes through a number of places where someone like Licona, Evans, or others claims there is a literary device at play and argues against this view. The chart above is a useful illustration of McGrew’s approach. Sometimes, she argues, there isn’t even an apparent discrepancy. The gospel authors having different sayings of Jesus on the cross is in no obvious tension. The conflict is only there if one reads overly woodenly.

Other times, the accounts are easily harmonizable. So, we should not resort to a complicated literary device. And on it goes.

One of the most interesting chapters is the final one on the resurrection accounts. There she shows that the differing resurrection accounts can be harmonized in an easy enough manner. Essentially, once we read rightly instead of woodenly and let people be people instead of figures in a play, the rest comes together quite naturally.

Conclusion

The Mirror or the Mask? is a really enjoyable read. Whether you want to work through the full book or jump around to read the parts that most interest you, this book is well worth your time.

Notes

[1] The Mirror or the Mask?, 26.[2] Ibid., 26.

[3] Ibid., 37; note: Licona thinks the Last Supper was a Passover meal.

[4] Ibid., 180.

I haven’t yet had a chance to read the book, but I very much doubt LeGrew’s thesis. Take the fact that in John’s Gospel, the ascension implicitly takes place before Jesus’ appearance to the disciples on Easter Sunday evening, while in Luke’s Gospel, the ascension takes place after his appearance to the disciples on Easter Sunday evening. There is a clear and major contradiction there (which is too big to be simply a memory lapse). The reason the ascension takes place beforehand in John can, however, be satisfactorily explained in light of John’s theological agenda. I don’t have the time… Read more »

Before commenting about a book, it would be good for you to read the book instead of using the comments to explain your theories and reject the book thesis by disguising them as a book comment. Duh.

By the way, the author is called McGrew, not LeGrew. It would be good for you to read the article before rushing to try to disprove it. Duh.

There’s nothing in John 20 which indicates an ascension before Easter evening. You’re probably referring to v17:

Jesus said, “Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my brothers and tell them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.”

Whatever you take Jesus to mean, the narrator certainly doesn’t say that Jesus went up to heaven then and there. In theory the narrator could even be asserting that Jesus said he was going to ascend immediately and then failed to ascend.