Reformed Epistemology (RE) is the view that belief in God can be rational without arguments. A growing number of theists are coming to adopt it–I’m one of them. One of the most common objections to RE is what’s been called “The Great Pumpkin” objection. I’ve seen it from atheists, I’ve even seen it from Christians. In this post I’ll explain why it is unpersuasive.

In his paper “The Reformed Objection to Natural Theology,” Alvin Plantinga articulates the Great Pumpkin Objection (GPO) like this:

The objection can be summed up like this: if we say that belief in God can be rational without arguments, aren’t we saying any belief can be rational without arguments, including the belief that some magical pumpkin returns every year for Halloween? The short answer is no; rejecting Classical Foundationalism doesn’t mean any belief can be properly basic. Now, unless you’re familiar with those terms already, the previous sentence won’t make a lot of sense. In what follows, we’ll take a closer look at properly basic beliefs (definitions and examples) and then move on to Classical Foundationalism (as well as some of the reasons Reformed Epistemologists reject it).

Proper Basicality

The idea behind Reformed Epistemology is that belief in God can be properly basic. Cool, but what does that mean? We’ll start with the basic part. A belief is basic when it is not held on the basis of any argument. My belief about what I had for breakfast this morning, for example, is basic. I simply think about it, remember that I had cereal, and then form the belief “I ate cereal for breakfast.” In fact, most, if not all, of our memory beliefs are basic; they aren’t held on the basis of any argument. (See the next section for more examples of basic beliefs.)

However, not every basic belief is properly basic. Properly basic beliefs are basic beliefs that are rational for a person to hold. Read that one again. Properly basic beliefs are basic beliefs that are rational for a person to hold. Most would agree that no one is rational in holding the basic belief “my next gamble at the casino will make me a millionaire.” As the saying goes: The house always wins. On the other hand, suppose I’ve just jammed my finger in the car door and find myself believing I am in excruciating pain. Hardly anyone would say my belief in this case is irrational. The latter is an example of a properly basic belief. It’s both basic and rational.

To say that belief in God can be properly basic is therefore to say that Theistic belief can be rational without any arguments.

Other Kinds of Basic Beliefs

In chapter four of Return to Reason (great book btw), Kelly James Clark explains how most of our beliefs are basic. Perceptual beliefs, beliefs based on memory, testimonial beliefs, belief in other minds, belief in elementary truths of logic, belief in induction (that the future will be like the past), mathematical beliefs, belief in an external world, and fundamental moral beliefs are all basic (see section 2 of chapter 4, “The Structure of Believings”).

Look at the image below:

Believe it or not, I took this at a wedding reception. To help tell the story, I usually step outside to take a picture of the venue. To my astonishment, this masterpiece happened to be going on right above the building. Think about all the colors you see in the image. There are reds, oranges, yellows, greens, blues, purples, and blacks. Pause a moment and think: Did you arrive at that list of colors by way of argument? Did you form a structured syllogism in your mind just now and conclude that there must be all those colors? Did you perform an abductive argument and conclude that your experience is best explained by the photo actually being that way? Probably not. Most likely you did what everyone does: you looked at the image and found yourself believing it looks a certain way. Perceptual beliefs are like that.

What’s more, think about how you knew you didn’t use an argument to arrive at your belief about the colors in the image. How do you know you didn’t use an argument? You simply remembered you didn’t. So your belief that you didn’t use an argument was not arrived at via argument. Memory beliefs are like that.

Do you believe that I really took that image at a wedding reception? If so, how did you arrive at that belief? You probably read what I wrote and believed it. Any doubt you might have about that belief is likely the result of my calling attention to it in this moment. Under normal circumstances, we simply believe what others tell us even when we can’t verify for ourselves that what they are telling us is correct. Testimonial beliefs are like that.

According to Clark:

Classical Foundationalism

Philosophers have long recognized the need to put our beliefs into two categories: some of our beliefs are basic, not held on the basis of argument, and others are non-basic, held on the basis of argument. Basic beliefs lie at the foundation of all our beliefs. They are what all our beliefs are based on. Classical Foundationalism (CF) is a view that helps us determine when a basic belief is rationally held or not. Classically, there are three criteria that basic beliefs must meet in order to be rational:

- Evident to the senses: beliefs that are the result of sensory experiences–like there is a computer in front of me, there is an orange hard drive on my desk, and so on.

- Self-evident: these beliefs are understood as true upon reflection–like 2+2=4, that there are no married bachelors, and so on.

- Incorrigible: these are beliefs we can’t possibly be wrong about–like it appears to me that there is a computer in front of me. (I could be wrong that there is a computer in front of me, maybe I live in the Matrix, but I can’t be wrong that it appears to me there is a computer in front of me–it is absolutely impossible I am wrong about that.) [1]

How is all this relevant? Reformed Epistemologists reject CF. More specifically, they reject the three criteria above as the only criteria for proper basicality (see [1]). Why? Upon closer inspection, CF commits suicide. We can ask: is belief in CF evident to the senses, self-evident, or incorrigible? Well, no. It meets neither of the three criteria. By its own lights, belief in CF can’t be properly basic. Thus, if the view is to be held rationally, it needs an argument. Are there any? Reformed Epistemologists are unanimous in saying no, there are no good arguments for CF. If they are right, CF commits suicide and must be abandoned. (Note: whether you agree or disagree with reformed epistemologists on this point is irrelevant since the GPO is a reductio.)

Back to Pumpkins

Last point of clarification–denying Classical Foundationalism does not mean denying all forms of Foundationalism. All it means is that those three criteria listed above are good, but they don’t tell the whole story. Here’s Clark again:

This is what Reformed Epistemology is all about; it’s a denial of Classical Foundationalism. Denying CF opens the door for belief in God (among other beliefs, like those based on memory). We are finally at the point where we can ask the original question. Does denying CF mean that any belief can be properly basic, including the belief that the Great Pumpkin comes back every year for Halloween?

Plantinga gives a helpful analogy to see why this doesn’t follow (beware, it is kind technical):

In the palmy days of positivism, the positivists went about confidently wielding their verifiability criterion and declaring meaningless much that was obviously meaningful. Now suppose someone rejected a formulation of that criterion-the one to be found in the second edition of A. J. Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic, for example. Would that mean she was committed to holding that: (7) Twas brillig; and the slithy toves did gyre and gymble in the wabe, contrary to appearances, makes good sense? Of course not. But then the same goes for the Reformed epistemologist; the fact that he rejects the criteria of Classical Foundationalism does not mean that he is committed to supposing just anything is properly basic (2009).

Now, unless you’re familiar with the philosophical jargon, the example above won’t be of much help. In the next section, I develop an easier analogy (skip there unless you’re a philosophy geek).

Logical Positivism (LP) held that if some statement can’t be verified by the empirical sciences, then it is meaningless. Interestingly, LP is now considered dead. Like Classical Foundationalism, Logical Positivism commits suicide. Can LP be verified by empirical sciences? No. So, if LP is true, then it is meaningless. Suppose, as Plantinga suggests, that we reject the verificationist criterion of meaning (as we should). Does it follow that his (7) is now meaningful? Not at all. Even without replacing the verificationist criteria, we aren’t forced to say that (7) has meaning. That doesn’t follow.

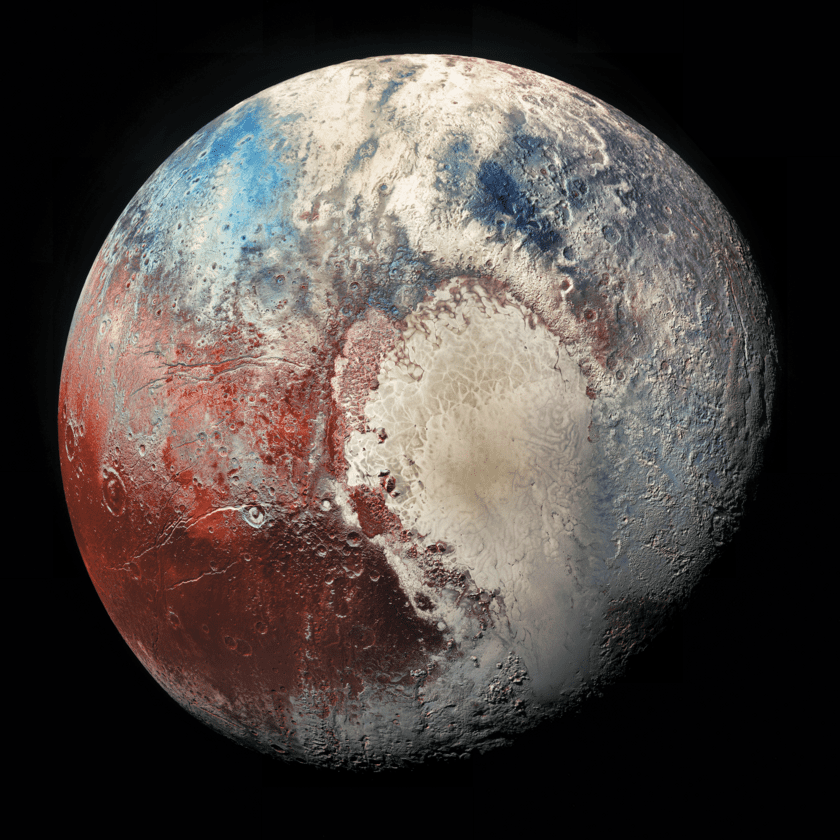

Pluto

Here’s another analogy you may find helpful.

If you’re like me, you were pretty upset when Pluto was declassified as a planet. The reason it was declassified is because it failed to meet one of three criteria laid out by the International Astronomical Union for full-size planets:

- It is in orbit around the Sun

- It has sufficient mass to assume hydrostatic equilibrium (a nearly round shape)

- It has “cleared the neighborhood” around its orbit

Pluto doesn’t meet the third criterion; it hasn’t “cleared the neighborhood” around its orbit. Suppose, however, that we found all three criteria problematic in some way (the reason isn’t relevant for the illustration) and thought it best to classify planets on a case-by-case basis using the other planets as our guide. This would mean that Pluto could then be considered a planet again. Yay! But then people might wonder: if we get rid of those criteria, does that mean that anything floating in space can now be considered a full-size planet? No, of course not. We can clearly see, for example, that a satellite is not a planet. Rejecting the criteria doesn’t mean “anything goes.”

Likewise, even without a rigid set of criteria for what constitutes a properly basic belief, we aren’t committed to the idea that any belief can be properly basic. That doesn’t follow.

Closing Thoughts

The Great Pumpkin objection arises from a rejection of the classical foundationalist criteria of proper basicality. Without a rigid set of criteria, how can we rule out aberrations like belief in the Great Pumpkin? Must we include any and all beliefs as properly basic? The way forward, argues Clark,

He goes on to say,

Essentially, the way forward isn’t unlike the situation with Pluto. Even without rigid criteria, we can inductively form a set of bodies we know are planets and use that as a guide for ruling out non-planets (like satellites). Likewise, we can inductively form a set of properly basic beliefs and use that as a guide for ruling out aberrant beliefs (like Great Pumpkins).

We’ll end with a quote from Plantinga:

This response doesn’t really move the needle in making reformed epistemology any more convincing. I can shorten this entire question and response as follows: Argument: “It seems to me, that with reformed epistemology, you can believe in ANYTHING and just claim it’s properly basic” This article’s response: “It’s possible that there are good reasons to accept certain beliefs as basic and reject others as basic” At the risk of sounding sophomoric, DUH! The possibility that good reasons might exist, does NOT mean that good reasons DO exist. The question “Why is it properly basic to believe God exists, but not… Read more »

Hi Nick. The argument wasn’t that it’s possible there is some good criteria of proper basicality we don’t know about, rather the argument was that CF is self-defeating and must be rejected. The question then becomes, without the CF criteria, which basic beliefs can be properly basic? You say that we must have criteria to determine this, but the conclusion of the article suggests otherwise. The way forward, according to Clark, Reid, and Plantinga, is inductive.

I hope this helps!

The objection to RE doesn’t seem to be that it *necessarily* commits one to actually holding these goofy basic beliefs, but rather that it doesn’t have an argument *against* someone doing it. So if someone claims that their belief in the Great Pumpkin returning every year for Halloween is properly basic, there’s little that someone who affirms RE could say to convince them otherwise (on pain of inconsistency). Same goes for any other unfalsifiable belief. So for example, when Plantinga says “… the same cannot be said for the Great Pumpkin, there being no Great Pumpkin and no natural tendency… Read more »

[…] Bertuzzi of Capturing Christianity recently wrote an article responding to the Great Pumpkin Objection to Reformed Epistemology (RE). While he explained […]

The analogy of Pluto was the one that made me understand! Thank you!